By now much virtual ink has been spilled about the racist comments made by Los Angeles Clippers owner Donald Sterling. I’m not going to draw any more attention to that. Instead, I want to focus on a pattern of racial discrimination lawsuits against Sterling, and on the complex and critical role that Asian Americans play in battles over race.

More disturbing and worthy of bigger news than Sterling’s verbal faux pas are the civil rights lawsuits that his real estate business has faced. Sterling is best known for owning the Clippers, but his wealth comes from real estate investments he made starting in the 1960s, in California’s depressed housing market. According to this detailed profile in ESPN, Sterling bought scores of apartment buildings between Beverly Hills and the Pacific Coast, and held onto them as the housing market boomed.

At the same time that Sterling was buying up real estate, California was embroiled in a political battle over race and housing. In 1963, the state passed the Rumford Act, banning racial discrimination in public housing in response to widespread discrimination. A year later, Californians voted 2:1 for Proposition 14, a ballot measure to repeal the Act. The California Supreme Court would later declare this unconstitutional and reinstate Rumford, but suffice it to say that the political history of race and real estate in California means that Sterling’s rise to riches was the result of his whiteness. Indeed, the California Real Estate Association, made up of white property owners like Sterling himself, launched Proposition 14, seeking to protect their investments against the declining market values that they feared black neighbors would bring.

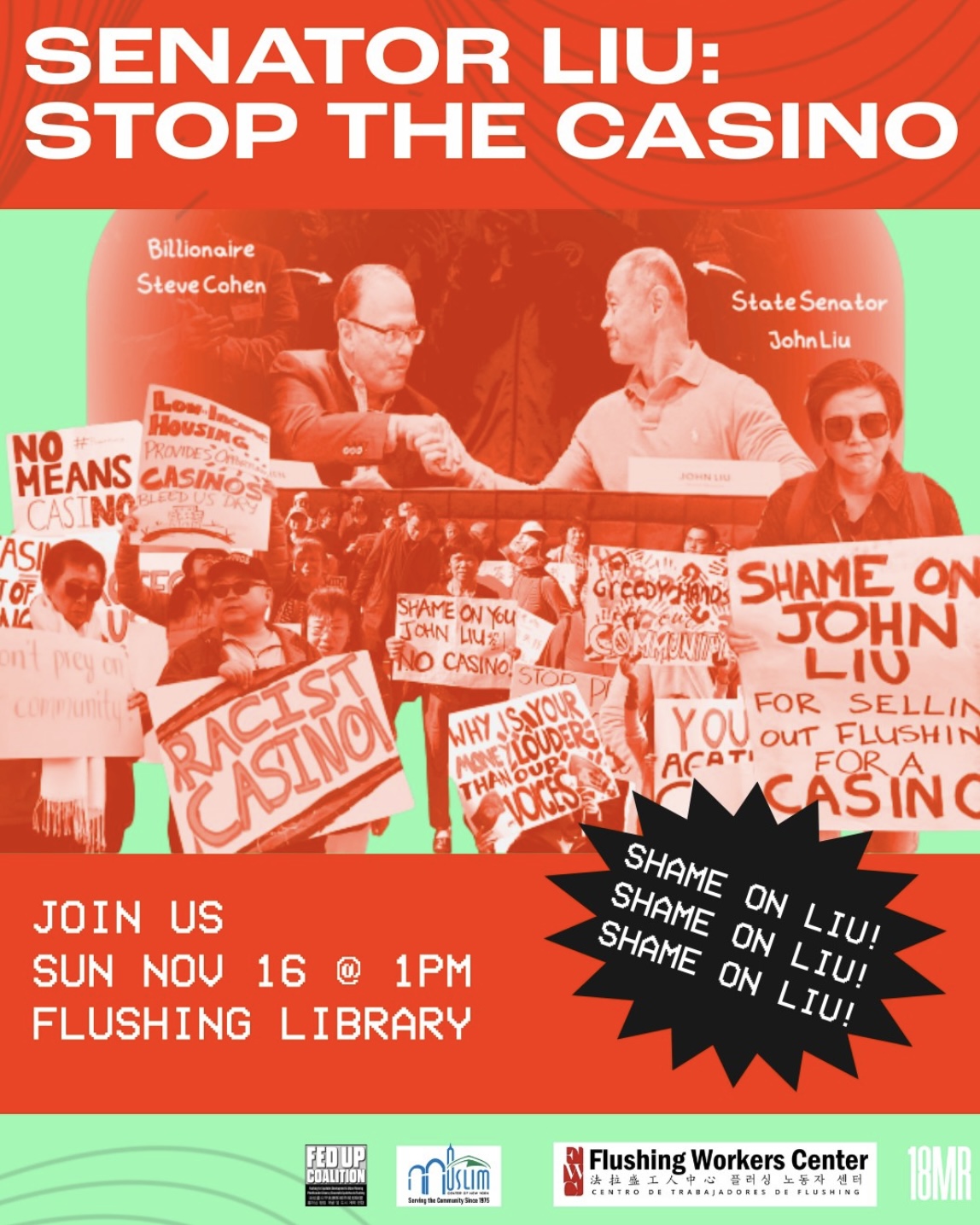

So it’s not surprising that someone who made his wealth from a system in which white landowners profited from racial exclusion might later engage in housing discrimination. The charges against Sterling’s real estate business have included refusing to rent to black and Latino tenants, but also preferring Korean American tenants. In 2003, the Housing Rights Center filed a lawsuit against Sterling with 19 tenants. It “accused Sterling of once stating his preference not to rent to Latinos because ‘Hispanics smoke, drink and just hang around the building.’ [It] also accused him of saying ‘black tenants smell and attract vermin.’” In comparison, an employee at one of Sterling’s properties reported him saying, “I like Korean employees and I like Korean tenants.” Another employee heard him say, “I don’t have to spend any more money on [Koreans], they will take whatever conditions I give them and still pay the rent.”

The case was settled in 2005, confidentially, for an undisclosed amount described by the judge as “one of the largest ever obtained in this type of case.” But judging from Sterling’s current net worth of $1.9 billion, it wasn’t large enough to shut down his profit-making ability.

A recent Slate article explored Sterling’s bizarre fascination for Koreans. It rightly chalks up the exception to his animus toward non-whites to the Asian American model minority myth:

At a basic level, he was buying into the myth of the “model minority”: the perception that Asian-Americans, compared with other nonwhite minorities, are innately intelligent and well-behaved… This is the flip side of a deeply held, racist worldview: Alongside the ‘undesirable’, vermin-attracting minority groups, there is another group that does everything right. Why did Donald Sterling idealize Koreans? Because, in his view, they did whatever Donald Sterling wanted them to do, and they did it without complaint.

The authors of this piece argue that the black-white binary is insufficient for understanding the model minority dynamics at play in Sterling’s racism. I disagree. The model minority myth was constructed to reinforce the black-white binary. For U.S. officials, incentives for creating the myth included gaining moral legitimacy for world leadership by showing racial tolerance, while also marginalizing black political protest. For Asian Americans, previously excluded from U.S. citizenship and immigration, there were real material benefits. Japanese Americans, who had recently been interned during World War II, actively participated in transforming Asians from despised Orientals into model citizens. And they did so by explicitly playing into anti-blackness.

So the fact that the Slate writers found no public complaints against Sterling by Asian American groups or individuals should not shock us, nor should the complicity of Sterling’s Korean-born guards in discriminating against non-Asian people of color. This is how the model minority myth works, and has always worked. It maintains systems of racialized advantage and disadvantage by rewarding assimilation to whiteness and justifying the criminalization of blackness. There have always been Asian Americans who have been complicit, and those who have resisted.

Notably, the exception to Sterling’s Asian American exception was his post-9/11 profiling of those believed to be, in the words of his staff, “foreign, I mean as Muslim, or, you know…” But this, too, is not surprising. The “yellow peril” – the idea of Asians as a foreign threat – is ever present as the model minority’s reverse. Not all Asians have the same access to model minority benefits, like white approval, upward mobility, and freedom from criminalization. Asians who commit crimes, who have disabilities, who are LGBT, or who come from nations with which the U.S. is at war, have limited access to these benefits.

The Sterling case also illuminates the politics of gender and sexuality built into the model minority myth. As the ESPN article explains, “In 2003 he had 74 white employees, four Latinos, zero blacks and 30 Asians, 26 of them women.” Sterling has faced at least two lawsuits for sexual harassment. In one, a female employee testified: “He would tell me that I needed to learn the ‘Asian way’ from his younger girls because they knew how to please him… If I made a mistake, I needed to stand at my desk and bow my head and say, ‘I’m sorry, Mr. Sterling. I’m sorry I disappointed you. I’ll try to do better.’”

The model minority demands conformity to specific gender roles required for maintaining the logic of straight, white, male domination. The idea of Asian female submissiveness is part of what makes the myth so potent in the white male imagination, by producing a sexually available, exotic, obedient female other who is definitively not black. The counterpart of course is the emasculated Asian male. Together, these ideas support the model minority profile – compliant, non-threatening, and not black.

Asian American political identity emerged during the radical social movements of the 1960s, taking inspiration from the Black Panther Party. This, too, shouldn’t surprise us, since Asians also faced racial discrimination and violence, including Alien Land Laws that barred them from owning land until 1952. The Asian American movement made important gains, including the fight for ethnic studies, alongside black-led racial justice struggles. Blackness has always been a part of Asian American racialization and political identity, and vice-versa.

As Asian Americans, how we organize for our rights matters. The model minority myth creates real incentives for remaining silent in the face of anti-black racism, but this obscures the ways that we have benefited from black liberation struggles, and how our struggles intersect. Complicity also costs us in political terms, by bartering away real solidarity on issues that matter to us, for shaky stakes in an unjust racial system of winners and losers. Beyond the issue of housing segregation, we are seeing this now in the fight over affirmative action. Conservatives are counting on us to be on the wrong side of the color line, and we should prove them wrong.

Guest blogger Soya Jung is a Senior Partner at ChangeLab, a grassroots political lab that explores how U.S. demographic change is affecting racial justice politics, with a strategic focus on Asian American identity.