People in my internet circles have been talking a lot lately about what white people think. Whether it’s the Whiteness Project, the new video interview series from Whitney Dow, or Bill O’Reilly, who adamantly refuses to acknowledge that white privilege is even a thing, it seems like we’re constantly critiquing, agonizing over, and scoffing at what white people think when it comes to race. For many young people of color, it’s so readily apparent that they’re wrong, even as people of all races are quick to claim a colorblind, colormute stance. Yet I’m pressed to find as much discussion about why these came to be dominant ideas about race and power.

There are straightforward truisms you can find in almost any corner of the left-leaning web, like how “privilege” also means the privilege to not have to think about race. But as we move through the fiftieth anniversaries of some of the most epic struggles and triumphs of the Civil Rights era, the question bears asking again, and the answer requires more than a string of Tweets or a thinkpiece.

This is the central work of Jeff Chang’s latest book, Who We Be: painting a picture of the why. And more than just what white people think, Chang is angling at what we all think—about ourselves and about each other, and how those ideas interact with the complex cultural landscape around us. His fifty-year epic charges headlong into the gap between high and low culture, exploring the places where power players and radical upstarts in fine art, advertising, politics, pop culture, and organizing brush elbows and intersect.

This is essential work. If neoliberal capitalism encourages, and relies on, our forgetting instead of remembering, Chang’s book is a timely act of resistance. As a member of a generation whose memory of political and public life begins during the Clinton presidency, Chang’s accessible yet expansive history of perceiving and performing race is a breath of fresh air. These are the cultural currents that have shaped the racial consciousness of people my age and younger—and they were designed by someone. It’s crucial to know who.

The narrative arc of Who We Be, populated by characters from pioneering cartoonist Morrie Turner to Republican strategist Lee Atwater, tracks the shift in where “conversations on race” take place. Fifty years ago, they were predominantly political-legislative questions, such as the landmark Civil Rights-era legislation to protect voting rights. Now, they’re market questions, driving advertising segmentation, which reaches its logical extreme in the big data tracking of the social web, where sociality itself is turned into a resource for extraction.

It’s no surprise that Mark Fisher’s capitalist realism, the concept that late capitalism has successfully absorbed everything up to the limit of the very horizon, haunts this progression: the market is both where we see the most earnest embrace of multiculturalism, but also the most striking examples of multiculturalism’s failed promise. If multiculturalism in the late capitalist marketplace looks like, simultaneously, the expropriation of the cultural production of people of color, and segmented marketing to communities of color, then all the representation in the world won’t be enough to save us.

Chang also carefully tracks the leftist pushback against multiculturalism: its opponents are not just far-right culture warriors, but also the far left, which sees through this market-based gambit. Who We Be turns our eyes toward persistent inequality, in spite of the apparent successes of cultural integration: near the end of the book, we literally find ourselves wandering in the high desert above Los Angeles, in the eerie, empty exurban community of Lancaster, where an astounding number of homes lie vacant, grappling with the conflicting forces of gentrification and the foreclosure crisis.

The primary weakness of Who We Be is the flipside to its strengths: the book is dizzying at times, and its focus on race allows it to merely edge at other categories of social difference, most notably gender and sexuality, that are always also at play when we talk about race, power, and privilege. It’s a tradeoff—the book’s just shy of 350 pages, moves at a furious clip, and I even get the sense there are more stories that Chang could tell that wouldn’t fit between two covers. If anything has been omitted, it’s not for lack of trying.

Who We Be is, most crucially, an incredibly timely book. Thoughtful scholarship wrapped in Chang’s accessible prose, we get pulled back from the minute detail of social media tit-for-tat. The landscape shifts into focus. Every argument is set against the backdrop that Chang paints in bold and evocative brushstrokes, and opens opportunities for new nuance.

Of course, these are deep, wide questions that can’t be tackled in a single volume. But Who We Be is one of the best places to start I’ve seen in a while: thoughtful, erudite, readable, and thoroughly entertaining.

Cayden Mak is Chief Technology Officer at 18MR.org.

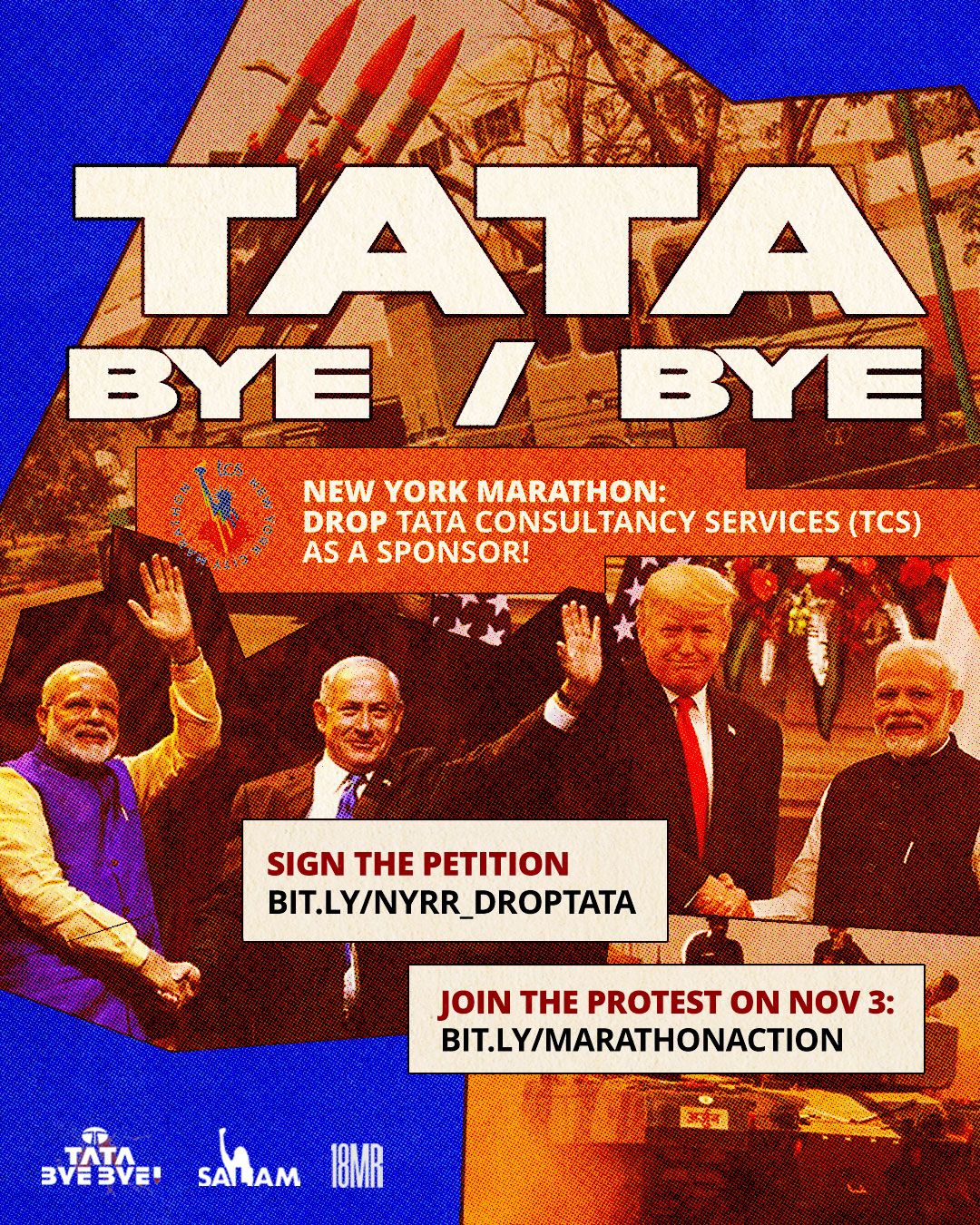

UPDATE 11/4/24 Download our FREE ZINE for you to print out, fold and distribute to your community. Though the Marathon is over, we still must inform […]

UPDATE 11/4/24 Download our FREE ZINE for you to print out, fold and distribute to your community. Though the Marathon is over, we still must inform […]