Hot summer Oklahoma sun. Brown Earth baked, cracked. Orange watermelon and big red tomatoes. Scissortails and Mockingbirds. We would name the stray cats that only came to eat and sleep under the old camper top. Kitty White Chest and Midnight. Grandma and me.

She would tell me who I was, even though I didn’t know it myself. Summer, Fall. Pumpkins, corn, beans, sofke. We are Creek. Lazy living room days. Picking biscuit dough from the tiny crevices of her silver-coral-turquoise rings on brown-skinned fingers. Looking at her Indian figurines, I wondered, is this me?

Was I the vanquished Indian, riding the horse whose head hangs low in the painting on the wall? Or was I the one that sifted the corn through Great Grandma Susie’s charred basket?

Sundays we would go to Thlopthlocco Church. The sermons were mostly in Mvskoke so I didn’t understand much. But that was OK ‘cause I recognized the big white blue-eyed painting of Jesus, framed, with locked gaze, staring at me in the center of the altar. He looked through me, no matter which angle I leaned. Sucking on peppermint candy I sat listening, arm-to-arm comparing my skin with Grandma’s. Then Jesus’.

Afterwards in the church kitchen that always smelled of leaking gas we would eat and I’d get a lesson on how my Grandma’s father, Thomas Harjo Dunson helped build the church. Her words were strong and proud and her smile, wide. His story told me who I was.

When we went to the community meeting place in town, she and my Uncles would commiserate with the elders and my eyes wandered to the tobacco and cigarettes for sale at the sundry store up front. I wondered how many quarters Indian was the RED MAN on the RED MAN tobacco bag? Because he didn’t look like my kinfolk at the table. Was I less Indian because I didn’t look like him?

What I didn’t understand then was that I was using an outside standard to judge my family and myself. My Indianness. These fake things seemed real to me; the pictures, the chew, the mascots, the frozen ceramic figurines, and I saw myself through the prism of their existence. As I was growing up and learning to navigate the often treacherous waters of American Indian identity, I am grateful for Grandma’s guidance, like an internal compass, always telling me which way to go.

And those that defend these depictions say things like, “you ought to be proud of the icon on the side of the helmet; for he is a handsome depiction of your people.” NO! I reject this image and standard-bearer. I will not be held captive by these false ideas, pictures and words. I get out and break free from the identity it wants for me. I know now that racism and assimilation played and continue to play dual roles in exploiting these images to dictate a false ideal. Add capitalism to the mix and you’ve got big business profiting from the commodification of these fabricated forms. Day after day, month after month, year upon year, costume after costume, game after game, over and over and over again with thousands of permutations of the same old thing.

Then I wonder, how would life have been different for Grandma and Mom, her sister and brothers, Grandma’s mother and father and all of us if we could have just been ourselves instead of living up to a quanta, a spectrum of colors, categories and images? Maybe then we would have learned to speak more Creek. Maybe then we would know more of the old ways. I can only guess, and yet, I have felt it my whole life. A quiet, loud, insidious oppression; hardly ever revealed but tangible all the same.

_Maggie Hundley, office manager/paralegal, is a 34 year old mother of two young girls and lives San Diego, CA. She is originally from Phoenix, AZ. She is a citizen of Muscogee (Creek) Nation, and currently active in Native social media activism. Her husband Kenton is a teacher at Southwest Key, a group home for undocumented, unaccompanied minors apprehended by INS.

If you’re moved by Maggie’s story, join us against Dan Snyder!_

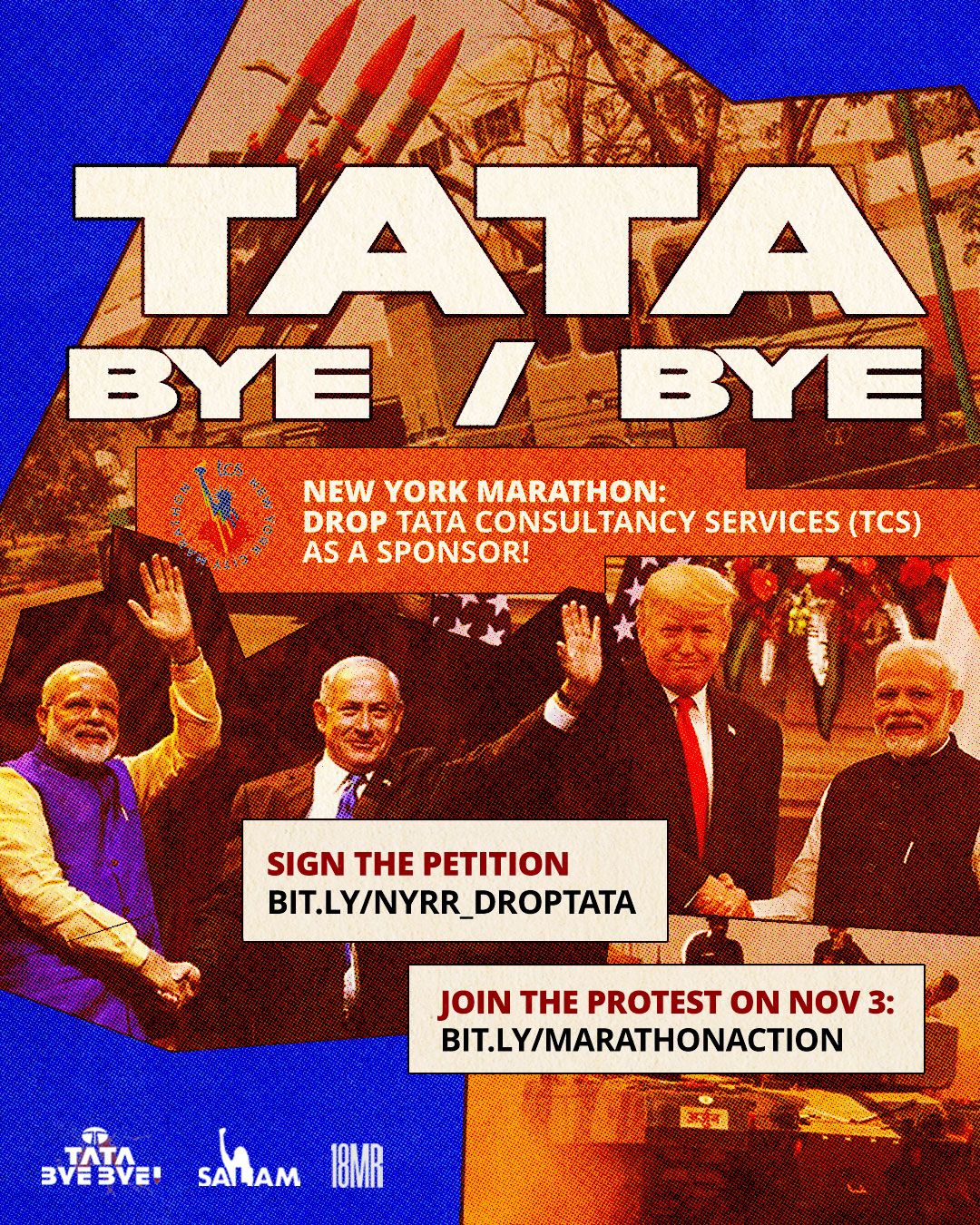

UPDATE 11/4/24 Download our FREE ZINE for you to print out, fold and distribute to your community. Though the Marathon is over, we still must inform […]

UPDATE 11/4/24 Download our FREE ZINE for you to print out, fold and distribute to your community. Though the Marathon is over, we still must inform […]