As we’ve been asking people to write in to protect Tule Lake, a National Historic Landmark in far northern California, we’ve gotten some questions about how Tule Lake is different than the monuments to Confederate military commanders being removed around the country. I wrote a response to a member who took the time to send us a thoughtful email wondering if preserving this history does more to give aspiring oppressors ideas rather than help us remember and mourn, and if so, if we should be trying to protect sites like Tule Lake.

Honestly, I can follow this logic, even if I disagree. We’re living in a time when the specters of the past are manifesting in the present in ways that are newly visible to a lot of people in our communities. People like Attorney General Jeff Sessions seem to be reaching backward to gather up precedents for codifying discrimination, structural violence, and disempowerment into the law, in both writ and practice. But there’s an important difference that this comparison elides.

The difference rests primarily in what and who these monuments remember. The Confederate monuments remember individuals who took up arms to prop up a racist system. I can see how these can be read – extremely charitably – as remembrances of past mistakes. However, they are ambiguous icons, at best. While they do recall a time of great historical injustice, they also glorify an individual who fought to defend that injustice. Imagine how different the conversation would be if these were monuments to people who rejected slavery and fought back, both enslaved and free. Instead, these monuments show proud images of the men who were willing to sacrifice their lives to preserve the plantation system of the antebellum South.

On the other hand, the sites of Japanese American concentration don’t glorify the people who made the decisions to send Japanese American families to prisons. We don’t see a statue of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signing Executive Order 9066, recognizing him for his sacrifices to “keep America safe.” Instead, these are places of quiet contemplation of the cruel things people do to one another, justified by racism. These sites do more to remember the ordinary people who lived through an extraordinary time. In much the same way as visitors to Auchwitz or Robben Island today are reminded of those incarcerated there, visitors to former incarceration camps are also reminded of the strength of the human spirit that played out in the struggles of the people imprisoned in those desolate places.

The images you choose to represent a historical moment matter – and putting up a statue to a supposed great man who committed atrocities is worlds away from preserving a place where the innocent struggled and in some cases died.

It’s also worth noting here that the effort to create monuments to Confederate war heroes is a relatively recent invention. Many of these statues didn’t go up during Reconstruction. However, during the rise of Jim Crow segregation in the early 1900s, and again during the Civil Rights era of the 50s and 60s, reactionaries who opposed civil rights and equality for Black people and other people of color wanted to create a social environment where the Confederacy was not seen as a shameful stain on the history of the South, but a proud part of its legacy. They chose to erect statues of these supposed war heroes. These statues often use the visual language of the equestrian, which we associate with a victorious conqueror, as a way of connecting the men who fought to preserve slavery with larger-than-life heroism.

Preserving Tule Lake is an antidote against another kind of revisionist history about the United States’ treatment of Japanese Americans during World War II. It urgently reminds us that we should remember FDR not just as the President who guided the nation out of the Great Depression and through World War II, but also the President who incarcerated hundreds of thousands of Japanese Americans for no other cause than racism, and whose 1944 GI Bill was designed to leave room for Jim Crow segregation, instead of guaranteeing the same benefits to both Black and white veterans.

There is a difference in the value of preserving sites like Tule Lake to remember, to mourn, and to remind us to never let such atrocities happen again. On the other hand, the Confederate statues being taken down across the country have always been props in a larger war against social progress. It’s important to remember the distinction.

You can join our campaign to #SaveTuleLake. Click here to send your letter to Modoc County by 10/10/2017.

Cayden Mak is Executive Director of 18MillionRising.org

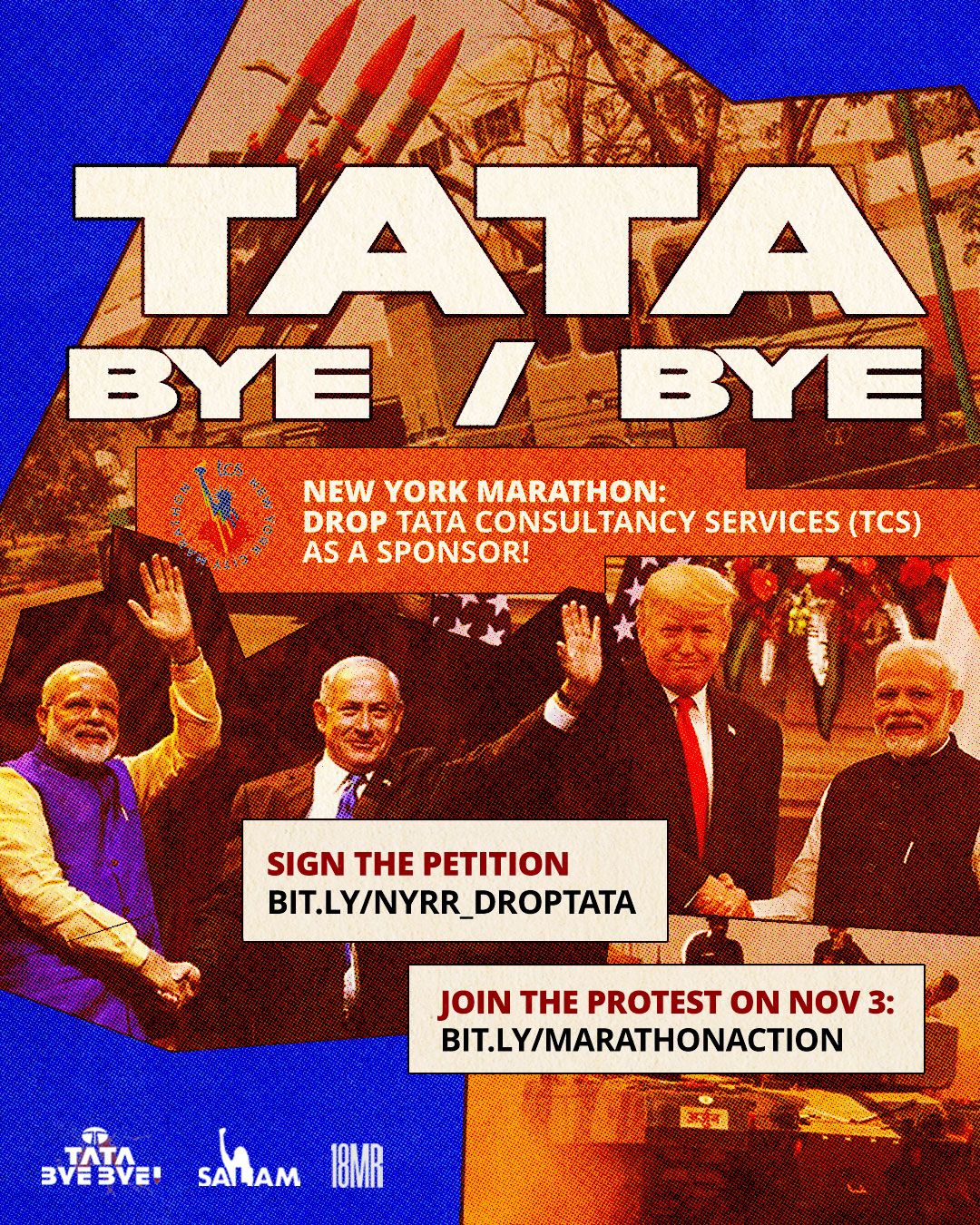

UPDATE 11/4/24 Download our FREE ZINE for you to print out, fold and distribute to your community. Though the Marathon is over, we still must inform […]

UPDATE 11/4/24 Download our FREE ZINE for you to print out, fold and distribute to your community. Though the Marathon is over, we still must inform […]